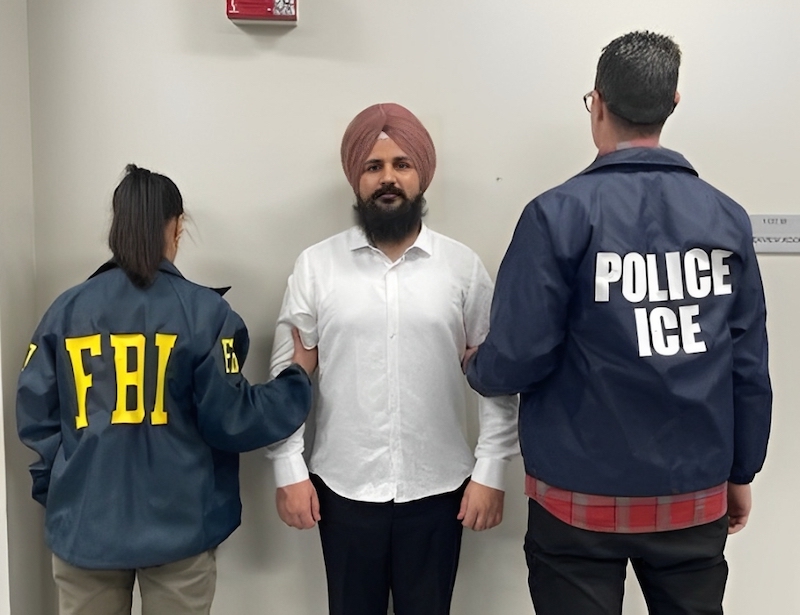

The Indus river flowing through a part of Ladakh. (Photo via Facebook)

The Indus river flowing through a part of Ladakh. (Photo via Facebook)

New Delhi: On April 23, India made the watershed decision to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan – a direct response to the devastating terrorist attack in south Kashmir’s Pahalgam that claimed the lives of 27 tourists and a local pony operator. Although Pakistani officials have denounced this move as an “act of war,” the immediate practical consequences remain largely symbolic due to India’s current infrastructure limitations that prevent any substantial alteration to water flows into Pakistan.

Nevertheless, should India embark on an ambitious infrastructure development program targeting the western rivers of the Indus system, the long-term implications could fundamentally reshape the geopolitical landscape of South Asia.

Read also: Pakistan’s suspension of Shimla pact – Symbolic move with limited impact

The Indus Waters Treaty and Its Suspension

The Indus Waters Treaty, signed in September 1960 with the World Bank as guarantor, has remarkably endured through three wars between India and Pakistan. This agreement governs the sharing of the waters of the Indus river system, allocating the eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej) exclusively to India, while giving Pakistan primary rights over the western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab). India’s rights on these western rivers are limited primarily to non-consumptive uses like hydroelectric power generation without significant storage capacity.

India’s decision to suspend the treaty came just a day after the Pahalgam terrorist attack, which New Delhi said it traced back to The Resistance Front (TRF) an offshoot of the Pakistan-based terror group Lashkar-e-Taiba. The suspension represents a significant shift in India’s strategic approach, leveraging critical water resources in response to continued cross-border terrorism.

Current Infrastructure Limitations

Although in the past the prime minister, Narendra Modi, hinted at taking such a step following the Uri attack in 2016, India did not take any concrete measure to follow it up. Rather, both Indian and Pakistani officials continued to meet and take forward the provisions of the water-sharing pact.

Now, despite the dramatic announcement on April 23, India’s immediate ability to influence water flow to Pakistan remains constrained by infrastructure limitations. Currently, India has several run-of-the-river hydroelectric projects on the western rivers but lacks the large storage reservoirs that would be necessary to control or redirect significant water volumes.

On the Chenab river, India operates projects like the Salal Hydroelectric Power Station, completed in 1987 after significant compromises with Pakistan that reduced its height, removed working reservoirs, and plugged under-sluices intended for sediment control. These compromises, made in the interest of bilateral relations, significantly weakened the long-term viability of the dam, which now operates at just 57% capacity.

Other existing projects include the Baglihar Dam, completed in two phases in 2004 and 2008, and the Dul Hasti hydroelectric scheme, a 390MW (megawatt) run-of-river project completed in 2007 after an extraordinarily long construction period (1989–2007). While these projects generate electricity, they have minimal ability to store or divert water.

A Decade-Long Endeavour

To convert the symbolic suspension into practical leverage, India would need to develop substantial storage infrastructure on the western rivers – a process that would likely take a decade or more based on historical precedents.

Large dam projects in India typically face extended timelines. The Tehri Dam on the Bhagirathi river, for instance, began construction in 1978 but wasn’t completed until 2006 – a span of 28 years. Even globally, megadams take an average of 8.2 years to build, often extending beyond 10 years. These lengthy timelines make dam projects particularly ineffective in resolving urgent energy crises and especially vulnerable to currency volatility, hyperinflation, political tensions, swings in water availability and electricity prices.

Currently planned projects on the western rivers include the Pakal Dul on Chenab’s tributary Marusudar (1,000MW), Ratle on Chenab (850MW), Kiru on Chenab (624MW), and Sawalkot on Chenab (1,856MW). Even if these projects were fast-tracked following the IWT suspension, they would likely take 7 to 10 years to complete based on historical construction timelines.

The Ratle Hydro Electric Project on the Chenab river, when completed, will have a total water capacity of 78.71 MCM (million cubic metres). However, even this capacity represents a fraction of the total flow of the Chenab river, limiting its ability to significantly impact water availability downstream.

Technical and Environmental Challenges

The geography of the western rivers presents substantial technical challenges for infrastructure development. The Chenab, Jhelum, and Indus flow through mountainous terrain in Jammu & Kashmir, making dam construction technically complex and expensive.

Environmental clearances represent another significant hurdle. For instance, one hydroelectric project in the region required environmental approval for 277.06 hectares of land, including 187.20 hectares of forest land. Such approvals are time-consuming and subject to rigorous scrutiny in India’s robust environmental regulatory framework.

Additionally, India’s aging dam infrastructure already requires significant attention. Of India’s 6,138 completed large dams, 1,065 are between 50 and 100 years old, while 224 are over a century old. The government has enacted the Dam Safety Act, 2021 and is implementing the Dam Rehabilitation and Improvement Project (DRIP) Phase II and III to address these concerns. This existing maintenance burden may limit resources available for new ambitious projects.

Strategic Calculation Behind the Symbolic Move

Despite its limited immediate hydrological impact, India’s suspension of the IWT represents a calculated strategic gambit with far-reaching implications beyond mere water management.

First, this decisive action signals a paradigm shift in India’s approach to cross-border terrorism. By leveraging a critical resource treaty in response to security threats, New Delhi demonstrates its willingness to deploy unconventional diplomatic tools against persistent terrorism emanating from Pakistani soil. This approach strategically internationalizes the cost of Pakistan’s perceived tolerance or support of terrorist groups operating against India.

Second, the move starkly illuminates Pakistan’s profound water vulnerability. The statistics speak volumes: nearly 80% of Pakistan’s irrigated agricultural land relies on the Indus river system, and over 90% of the country’s food production depends on irrigation drawn primarily from these waters.

Pakistan’s precarious water situation has deteriorated dramatically, with per capita water availability plummeting from 5,600 cubic meters at independence in 1947 to barely 1,000 cubic meters today – officially placing the country in the water-scarce category. This dependency creates a potent strategic leverage point that transcends conventional diplomatic or military pressure.

Third, Pakistan’s severe reaction – characterizing the suspension as an “act of war” and retaliating by suspending the 1972 Simla Agreement – reveals the profound psychological impact of India’s decision. This disproportionate response demonstrates how even largely symbolic measures can generate significant diplomatic leverage when they target fundamental vulnerabilities.

From Symbolism to Substance

Transforming this symbolic diplomatic manoeuvre into concrete strategic leverage would necessitate a comprehensive, multi-year infrastructure development strategy. For this transition to succeed, India must pursue a four-pronged approach:

1. Expedite completion of existing planned projects on the western rivers, initially adhering to technical parameters previously permitted under the IWT to maintain international legitimacy while building capacity

2. Develop ambitious new master plans for storage infrastructure that capitalize on the suspension of treaty restrictions, prioritizing projects with maximum strategic impact and minimal ecological disruption

3. Mobilize substantial financial resources – potentially exceeding tens of billions of dollars – through innovative funding mechanisms, international partnerships, and dedicated infrastructure bonds

4. Navigate India’s robust but complex environmental clearance framework while balancing ecological concerns with strategic imperatives

Should India maintain steadfast commitment to this approach over the coming decade, the initially symbolic suspension could evolve into tangible control over Pakistan’s water security. However, such a transformation demands extraordinary political continuity, strategic patience spanning multiple electoral cycles, and steadfast public support for what would constitute one of India’s most consequential infrastructure undertakings since independence.

The China Factor

Beyond India’s current infrastructure limitations for damming or diverting the Indus river system, New Delhi confronts a far more formidable challenge in implementing the IWT suspension – China. Beijing’s conspicuous absence from the Indus Waters Treaty introduces probably the biggest geopolitical variable into India’s hydrological strategy. As the supreme upper riparian power controlling Tibet – aptly called the “Water Tower of Asia” – China commands the headwaters of both the Indus and Brahmaputra rivers, providing it with unparalleled leverage over downstream nations.

When India and Pakistan negotiated the IWT in 1960, China’s territorial claims over Tibet – and consequently, the Indus’s origins – remained entirely unaddressed, creating a strategic blind spot that has grown increasingly consequential with China’s rise as a regional hegemon.

Beijing’s growing dam-building spree on transboundary rivers underscores this vulnerability. On the Indus, China has already constructed multiple dams in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), including the Diamer-Bhasha Dam, which India views as illegal. These projects not only legitimize Pakistan’s claims in disputed territories but also enable China to regulate water flows before they even reach Indian-controlled areas.

The Brahmaputra basin reveals parallel risks. While 80% of the river’s water originates in India’s Arunachal Pradesh, China controls the Tibetan headwaters and has built 11 dams on the Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra’s upper reaches), with plans for a megadam capable of diverting 60 billion cubic meters annually to arid northern China. Such diversions could reduce downstream flows by 20% to 30%, directly impacting India’s northeastern states and Bangladesh.

Critically, China’s refusal to sign any transboundary water-sharing agreements allows it to weaponize hydrological data. Despite bilateral memorandums, China routinely withholds real-time river-flow information from India – a ploy evident in its repeated claims that monitoring equipment on the Brahmaputra “washed away” during monsoons. This opacity complicates flood forecasting and infrastructure planning for lower riparian states.

For India, the dual challenge lies in countering Pakistan’s water grievances while mitigating Chinese upstream dominance. Any attempt to restrict Indus flows to Pakistan could prompt Beijing, Islamabad’s all-weather friend, to retaliate by accelerating dam construction or reducing Brahmaputra flows – a scenario that would compound India’s water stress. This triangular dynamic transforms water into a multi-front strategic liability, where India’s leverage over Pakistan remains constrained by its own vulnerability to Chinese hydrological coercion.

Conclusion

There’s no doubt that India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty marks a watershed moment in South Asia’s geopolitics, which blends symbolic posturing with long-term strategic recalibration. While the immediate hydrological impact on Pakistan remains limited due to India’s infrastructure constraints – a reality underscored by Pakistan’s continued access to 80% of the Indus system’s waters – the move signals New Delhi’s willingness to weaponize shared resources in response to cross-border terrorism. This is despite historical precedents suggest that developing storage infrastructure on the western rivers could take a decade or more, given technical complexities and environmental hurdles.

However, the China factor complicates this calculus exponentially. As the upper riparian controlling the headwaters of rivers originating in Tibet and China’s unilateral dam-building on the Indus and Brahmaputra introduces a dual vulnerability for India. Beijing’s existing projects in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and planned diversions on the Yarlung Tsangpo threaten to neutralize India’s leverage over Pakistan while compounding water stress in India’s northeastern states.

Therefore, as mentioned earlier, it transforms water into a multi-front strategic challenge, where any Indian action against Pakistan risks provoking Chinese countermeasures.

Ultimately, the treaty’s suspension underscores the erosion of hydrological diplomacy in an era of climate volatility and security-driven realpolitik. While Pakistan’s agriculture and energy sectors remain theoretically vulnerable – with 70% of its economy tied to the Indus basin – India’s capacity to capitalize on this hinges on infrastructure timelines and China’s countervailing actions.

The coming decade will test whether water becomes a decisive tool in regional statecraft or a cascading trigger for broader ecological and geopolitical crises.