The India-Tibet border with disputed territories marked in yellow.

The India-Tibet border with disputed territories marked in yellow.

India and China never shared a common border until China annexed Tibet, a process it started in 1950. This brought the dragon right to our doorstep. With its annexation of Tibet, Beijing rejected the earlier border, the McMahon Line, which has a clearly drawn boundary. The 1914 Simla Convention between British India, the Tibetan government, and Tibet’s overlord – Republic of China, agreed on this boundary with clear coordinates. However, the Tibet government disputed the part of the agreement which dealt with the demarcation of the areas under the Tibetan government’s authority, aka, the Blue Line, and those directly under Chinese administration. This was the reason why Ivan Chen, the Chinese representative, didn’t sign the final agreement.

In the 1962 border war with India, China annexed large parts of Indian territory in our northern borders and consolidated its positions on territories that it slyly occupied, like Aksai Chin in India’s north and some areas in Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. Although it faced a military defeat during the 1967 Nathu-la/Cho-la incident in Sikkim, it embarked on a campaign of salami-slicing Indian territory, wherein they would move just a few hundred metres at a time, settle Tibetan nomads and then later claim the area as their own.

Today, China has illegally occupied thousands of square kilometres of India territory along the 3,488-kilometre line of actual control (LAC) by this method – from Ladakh in India’s north to Arunachal Pradesh in India’s east.

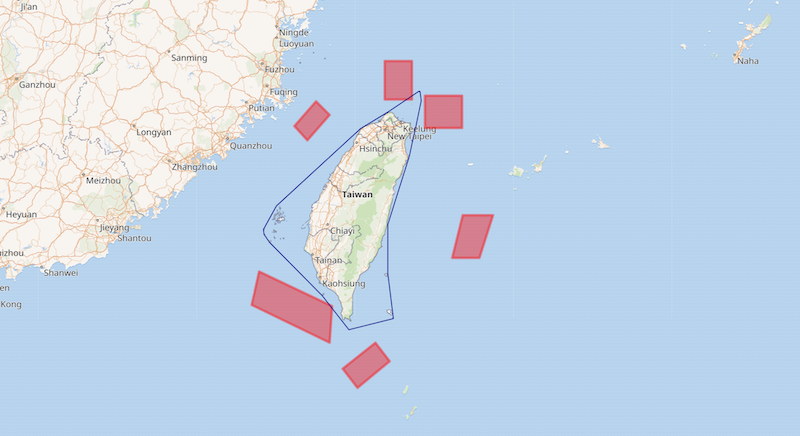

After the Doklam stand-off in Bhutan, in which China was made to retreat, China started making brazen moves to occupy Indian territory. In 2020, China slyly moved troops inside our side of the LAC and occupied strategic positions. This resulted in a long and tense stand-off, which also saw deaths of Indian and Chinese soldiers during a club-and-fist brawl. Now, both sides have mobilized a huge number of troops and military hardware in the area. This is draining the economy of both the countries and is hurting both, especially when the Covid-19 pandemic has taken a heavy toll on both the economies.

This calls for an early settlement of the border dispute amicably. And it is possible.

Although the India-China border issue is a shared legacy from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whose origins can be traced to the British and Russian expansion in Central Asia in the early 20th century, the border dispute since the 1950s has cast a deepening shadow over relations between the two nations, epitomized by the border war of 1962, scars of which are yet to heal, at least on the Indian side.

However, since the 1980s, the Chinese and Indian Governments have made attempts to resolve the border dispute through diplomatic negotiations. Frustratingly, the dispute stands exactly where it did when it emerged more than half a century ago, largely due to the rigid and unchanging stance of both countries. In fact, the negotiations can be termed as numerous rounds of “fruitless talks”, with each side claiming large parts of the other’s territory.

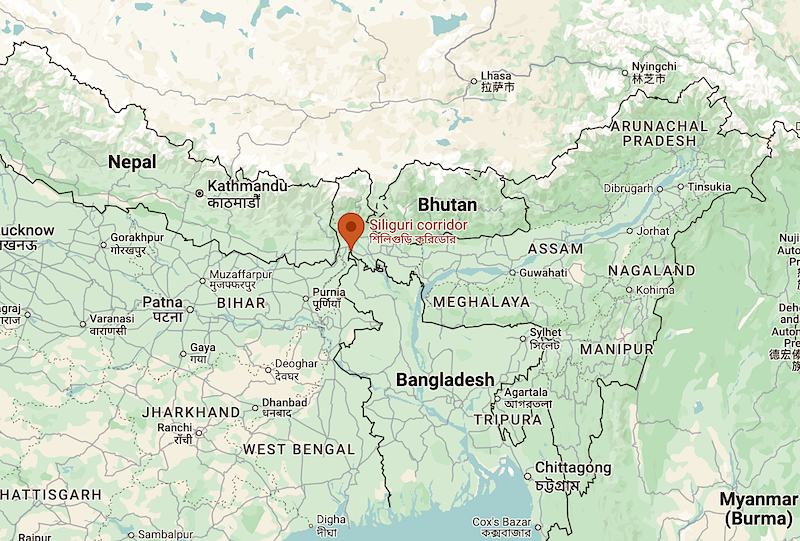

The non-settlement of the India-China border is certainly not due to lack of diplomatic efforts. However, it is enigmatic, because China has resolved its land border disputes with all its neighbours, except India and Bhutan, whose foreign policy has umbilical links with India. This dispute is turning out to be one of the most laboured one in history; an unresolved border conflict which periodically erupts into phases of open and intense rhetorical confrontation in the frontiers, like Depsang, 2013; Chumar, 2014; Demchok, 2014-15; Burtse, 2015; Doklam, 2017; Galwan, 2020; etc.

If left festering on its own, this dispute has the potential of spiralling into an armed conflict between two nuclear powers, providing the Chinese with a convenient casus belli for a war against India. With a current GDP of $14.7 trillion (nominal), China's economy would surpass the US around 2027-28. India being only a $2.7 trillion economy, the cost of any skirmish or battle or war with China due to long pending border disputes will always be severe and hurt India more than China. Furthermore, it would divert our comparatively meagre resources from much needed Socio-economic development. Of late, China also has been seen to be shifting/changing its “goalposts” to the erstwhile “package proposal”, which is rendering future negotiations untenable and impossible to settle for a lasting solution to the border dispute if we do not address it proactively. Therefore, it is only imperative on the part of India to seek early resolution of the border dispute with China so that the national efforts are rightfully diverted towards economic development.

It is also a matter of historical evidence in the border dispute that both the countries have major claims and counterclaims in western and eastern sectors, the minor one being in the middle sector. In the western sector, China is holding on to 38,000 square kilometres of territory in Aksai Chin which has been claimed by India. In contrast, India is in possession of 90,000 square kilometres of territory in Arunachal Pradesh, which China claims as part of their “Southern Tibet”. Here, China covets the Indian town of Tawang and the region around it the most. What obviously stands out is that, firstly, the border between India and China is definitely unsettled; secondly, it has resulted in claims and counterclaims by each country of areas held by the other; and thirdly, from the view point of a neutral observer, India appears to be the beneficiary, being in occupation of more land (90,000 square kilometres) claimed by China than China itself, which as per India, is in occupation of 38,000 square kilometres of Indian territory.

It is only axiomatic to highlight that the prerequisite for a border settlement with China should be a desire for one. The circumstances must be such that China is ready for meaningful negotiations. For India, it is in a position of sufficient military, political and economic strength; so that it becomes necessary or advantageous for China to make up with India. The advent of such a situation may take a very long time or may never occur. Thus, taking a middle path, or making concessions, a process of “give and take” may be the only way forward in amicably resolving the vexed India- China Border issue like the way the century-old issue of exchange of enclaves was settled between India and Bangladesh on August 1, 2015, despite India being in a disadvantageous position and profile in terms of number of enclaves and total land only for larger good of people of the two countries.

A cursory study of the history of India-China border talks since the 1950s clearly indicates that in all these years China has made several proposals, whereas India is yet to put across a single proposal.

In reflection, it is the Chinese who initiated the Peace and Tranquillity Agreement of 1993; and the indirect impact is there for all to see – the entire Indo-Tibetan border has become disputed instead of a few pockets and now converted into the LAC.

To make a sincere attempt at resolving the boundary question, the Indian side needs to take more proactive steps, since advantages accruing to India would far outweigh those accruing to China. With this as the underlying factor, it is essential that “out of the box” solutions be thought of keeping in mind Chinese sensitivities and concerns.

In the power politics of the present-day global geopolitical environment, we should use maximum leverages available, concurrently making an irresistible offer to the Chinese. Keeping in view Indian standing within the comity of nations as a responsible and rational power, project Indian reasonableness and place the ball firmly in Chinese court.

Out of many options available, assuming that a quick and early settlement in the middle sector would be achieved being with a very minor claim/counterclaim, the middle-path option, in which boundary in the western sector is proposed to be along the Macartney-MacDonald Line while in the eastern sector the Chinese to forego their claim on Arunachal Pradesh as a quid pro quo is a most practical and viable course and recommended to be applied for early settlement of borders between India and China.

While the above proposal may or may not be accepted by the Chinese or even our own country for a meaningful outcome, the same, however, would enable us to commence a humble but a progressive step towards a lasting settlement in a historic border dispute between two countries. Furthermore, depending on the progress made in the negotiations of the above proposal, it would only be prudent and pragmatic for the country to keep the options open in all stages of negotiations and keep revising the goal post by taking the Nation into confidence, including the existing China's claimed lines in western sector by creating buffer zones at all existing and potential friction points as has been applied in north and southern banks of Pangong-tso (Pangong lake) as well as the Gogra Hill and Galwan (PP14).

Therefore, it is only stating the obvious that the final outcome will be a matter of progress made by a process of sustained and hard bargaining besides deft negotiations over a period of time. Concurrently, besides being taken into confidence right from the beginning and through the entire process of negotiations, the leadership of all political parties must be conducted through a “change management” to stay the course with focus and resolve and reach a final settlement of the border dispute between two countries.

It is a well-acknowledged fact that India missed an opportunity in the 1960s to permanently resolve the boundary question by turning down the Chinese package proposal, in which the essence lay in an east-west swap, generally corresponding to status quo possession. Apart from that, another opportunity was missed when China’s supreme leader Deng Xiaoping offered a package proposal that was made officially to the-then foreign minister, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, during the latter’s visit to China in 1979. Deng made another offer, in 1988, when the-then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, visited China.

India didn’t even bother to respond to it.

Since then, China has begun to shift its goalposts and modified its earlier claim to include Tawang in addition to the western sector. Essentially, the boundary question in the earlier three packages was reduced to a dispute over two areas of unequal importance – Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh – in which India gained as it was in possession of territory that was larger, inhabited and endowed in comparison with what China had.

The Chinese view that a holistic settlement based on the exchange of claimed territories in the two sectors would permanently resolve the issue, subject to minor adjustments in places. Today, India stands at a distinct disparity in capacity, capability, and comprehensive national power (CNP) vis-à-vis China, with very low probability of the gap closing in the next few decades.

This leaves India with no choice but to negotiate by a process of “give and take”. However, what stands as a major roadblock is lack of political will, caused mostly by the 1962 Parliament resolution. Possibly the only way out of this impasse would be to take a political decision to resolve once and for all the India-China boundary question, even if it entails making territorial concessions. However, the most important ingredient that has emerged for India making this type of disadvantageous settlement would be shaping the perception of the population at large.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect the views of India Sentinels.

© India Sentinels 2021-22