INS Vikrant

INS Vikrant

The fascinating story of INS Vikrant’s role in bringing the 1971 war to a conclusion in India’s favour.

Heating the iron

1971 was an eventful year for the Indian subcontinent. In this year, Amitabh Bachchan got his first Filmfare award. And, erstwhile Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) saw an unprecedented violence in the wake of an attempted Marxist revolution and counterinsurgency crackdown by the state.

The year also witnessed the first hijacking of an Indian commercial airliner. Two Kashmiri militants took an Indian Airlines flight (Ganga) to Lahore at gunpoint and burned it on the tarmac in January. Later, it was claimed that the hijacking was orchestrated by Indian security agencies. The subcontinent saw its first air-hijacking that day and the menace haunts us till today. But more relevant for the time being was the resultant Indian ban on all kinds of Pakistani aircraft flying through Indian airspace.

The year also saw a secessionist movement in East Pakistan, met with a state-sponsored genocide on a hitherto unprecedented scale, by the Pakistani security forces (Operation Searchlight), in March.

Actually the last two incidents were interrelated. Together, they would bring us to that fateful night of December 2, on the bridge of INS Vikrant, when the signal “Open Sangsar” was received and started the aircraft carrier on its mission to create history – and geography. This story will tell us what happened next, and how the birth of Bangladesh was facilitated by Indian naval battle group Vikrant’s blockade of the Bay of Bengal.

What was the 1971 war all about?

Bengali nationalist opinion in East Pakistan had become increasingly alienated from the West Pakistani ruling elite since the early days of our blood-soaked independence. Sheikh Mujib and his Awami League had been in touch with Indian intelligence agencies for years, since the 1965 war. The “Agartala Conspiracy and Sedition” case of 1968, against Mujib and 34 others brought out in the open the intense craving for a separate national identity for East Bengalis.

An increasingly assertive Indian government wanted to make full use of Bengali discontent, as a riposte to Pakistan’s, decades long, meddling in J&K. The 1970 Pakistan National Assembly election saw an overwhelming victory for the Awami League. In the east, they polled 75 per cent of all votes cast. When the West Pakistani Punjabi elite refused to allow Mujib to stake claim to form a government, all hell broke loose in the eastern part of the country.

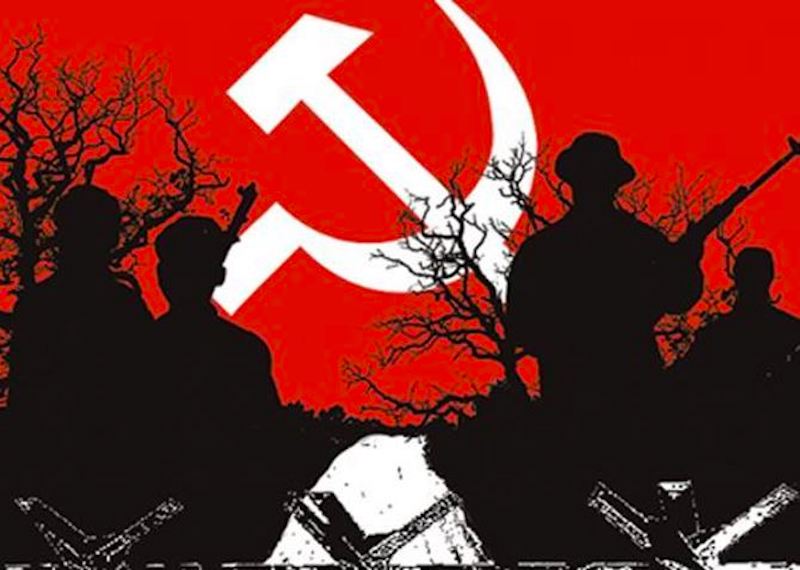

The tipping point had come when the Bengalis rebelled and the Pakistani establishment cracked down with unprecedented cruelty. While the real toll of the brutal crackdown could not be ascertained as yet, speculation is that it took millions of human lives. Mujib declared secession of East Pakistan to form an independent Bangladesh. Most of the Bengali troops of the Pakistani armed forces, stationed in the east, rebelled against the establishment leading to pitched battles and massacres. As the much more powerful and better equipped Pakistan Army pushed the ill-equipped Bengali regular units back towards the Indian borders, there arose the civilian guerrilla units of the Mukti Bahini.

Some skeletons of Bengalis killed during Pakistan’s genocide in East Bengal.

Some skeletons of Bengalis killed during Pakistan’s genocide in East Bengal.

Through the ebb and flow of the Mukti Bahini’s fortunes in the field, India remained steadfast in its support and resolve to facilitate the formation of an independent Bangladesh. This issue needs to be underscored here. The 1971 war was not a typical subcontinental border skirmish and short campaigns with cautious shallow incursions. Nor was it a limited, punitive move like the PLA’s drive in 1962 to teach India a “political lesson”.

The 1971 war was one of the few post-World War II military actions meant to significantly alter geostrategic realities on the ground. It created a new independent nation of 148,460 square kilometres, which is larger than Greece or England. Yes, India’s 1947–1949 campaign in Jammu & Kashmir had saved substantial parts of the state from foreign occupation, but the scale of combat is in no way comparable.

The Indian government and the armed forces were well prepared turning the riverine coastal state of Bengal into a mammoth water sports fantasy through summer and long monsoon. The Pakistanis knew what was coming, but their build-up was hamstrung by the Indian ban on Pakistani aircraft flying over India en route to the eastern wing. So, all their logistics were routed through the long and circuitous route via Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

Pakistan People’s Party leader ZA Bhutto greeting the hijackers of Ganga at Lahore airport.

Pakistan People’s Party leader ZA Bhutto greeting the hijackers of Ganga at Lahore airport.

The Indian government under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and its foreign intelligence agency RAW, had made their moves like chess grandmasters. The brilliant intelligence coup, with that staged hijack of Indian Airlines’ (IA) Ganga in January completely foxed Pakistan. Their public opinion was jubilant and the authorities welcomed the “liberation fighters of Kashmir”. But soon they realised that they had been suckered by the Indian security establishment. East Pakistan was isolated and on the boil politically.

When the Mukti Bahini stepped up its insurgency, it led to a spiral in the violence consequent repression. Pakistani army units went on wide sweeps in the countryside, “living off the land”. This euphemism for running wild amid the local population led to systematic torture, massacres, rape on an industrial scale and the attempted ethnic cleansing of the local minorities. Ten million refugees fled to India.

A Mukti Bahini training camp.

A Mukti Bahini training camp.

Politically, the situation was ripe for Indian intervention in East Pakistan. The “Indo–Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation” signed in August 1971 cleared the decks for the final move.

From November 11, the Indian forces, already in control of the bordering areas inside East Pakistan, started expanding their bases and launch pads deeper. This led to air and tank battles for the first time since the 1965 war. In the Boyra salient on the Jessore axis, on November 21, the Indian 4 Sikh Battalion (ex-350 infantry brigade) threatened Chaugacha (Chowgacha) (grid ref: QT9169) across the Kabadak river. Their crossing was resisted strongly by the Pakistanis from prepared defences. While the Indian 14 Punjab battalion (ex-42 infantry brigade) with 14 tanks (C squadron of 45 Cavalry Regiment) were already across the river and met a Pakistani battalion sized attack (6 Punjab, ex-107 infantry brigade), supported by the 3rd Independent Armoured Squadron, around Garibpur village (grid ref: QT9465).

The Pakistanis were thrown back with heavy losses. Their 3rd Armour was nearly wiped out with 11 tanks knocked out. The PAF was used extensively in this operation by the Pakistanis. However on this count too they suffered reverses. On 22nd, a flight of 3 PAF fighters, dive – strafing Indian positions in this area, were surprised by four low flying IAF fighters and all three were hit. Two crashed in the nearby area and one limped back to Dacca (now Dhaka) trailing smoke.

This is where the first Pakistani prisoners of war of the 1971 war was taken by then Captain Harcharanjit Singh Panag, the battalion adjutant of 4 Sikh. It was a historic development. Lieutenant General Panag, who went on to become the commander of the Indian Army’s Northern Command and is now retired, has written his own account of this episode.

Indian defence minister Babu Jagjivan Ram after the battle of Garibpur, visiting the forward areas. (Photo courtesy: Brigadier Balram Singh Mehta/Anurag Biswas)

Indian defence minister Babu Jagjivan Ram after the battle of Garibpur, visiting the forward areas. (Photo courtesy: Brigadier Balram Singh Mehta/Anurag Biswas)

Over to the Navy: Stories told and untold

All official records of the war agree on the sequence of events that followed. On November 23, President General Yahya Khan declared a state of emergency in Pakistan, telling the nation that Indians are coming, and it means war. We Indians got the news of the Pakistani, supposedly “surprise”, air strikes against our forward airfields in Punjab on the evening of December 3, 1971. That’s when the war officially began. But was that actually a surprise? Our readers can see for themselves as the narrative unfolds.

We now take you over to a very critical component of India’s operational plans for the 1971 war executed by the Indian Navy. This story will throw some light on certain, relatively lesser known, aspects of these operations and also on some fascinating details from the decks.

This is where INS Vikrant, the Indian Navy’s only aircraft carrier, makes its entry into the plot. It was an ageing vessel launched as the Majestic-class HMS Hercules just after World War II and lying incomplete for many years considered “surplus” during Britain’s peace time constriction of its armed forces. Finally, the Indian Navy commissioned its completion and it formally came into service in March 1961 just before the Liberation of Goa.

The writing is on the wall

INS Vikrant was in anchorage at Bombay in July 1971 when the war clouds gathered on the subcontinent’s skies. Indian decision makers had made up their minds and the ducks were being lined up. As the month of July progressed things got moving on board Vikrant. They had visitors. Babu Jagjivan Ram, the defence minister, arrived with the flag officer commander in chief, Western Naval Command, Vice Admiral SN Kohli, and the top brass from the Western Fleet. The minister stood on the modest podium and gave an impressive speech, first in English and then repeated what he said in Hindi.

He spelt out the geostrategic situation, compulsions and military challenges facing India at that moment. He didn’t mention war in so many words, but everyone got the message right. Recalling the speech, veterans say that they were impressed by Ram’s clarity of thoughts and precision with words. And the fact that the minister could convey his exact thoughts and message in Hindi after speaking the same in English without consulting any notes or without the aid of any teleprompter reflected that he knew what he meant.

Then Rear Admiral EC Kuruvilla, the big imposing Western Fleet commander, took over. He blandly said that INS Vikrant was being sent to the east. “If you stay here you will get sunk, and in the east, if you don’t work hard, you will get sunk there too!” And with that, Vikrant had its sailing orders.

The concerns with INS Vikrant were genuine. The ship had never participated in any operation till then, except for a minor role in the liberation of Goa (1961). During the 1965 war with Pakistan, it served in maintenance and refit. By 1971, it had been decided that all its four boilers would need to be replaced. But as the situation rapidly escalated in the course of the year, the replacement programme had to be done away with. It was found that only three of the boilers could be made functional and the vessel would have to make do with that reduced power. It meant a reduced cruising speed of 14 knots. At a pinch, they could do 16 knots during “Flying Stations” (launching aircraft from the decks).

Now for a carrier, speed mattered not just for mobility but also for its aircraft to be able to be launched safely. Carrier-borne aircraft need the vessel to travel ideally at around 20 knots, if there was low wind speed, to take off safely. Therefore, if the carrier’s speed is restricted, it would require a rather strong tailwind for successful flight launches.

Leaving for the East

They left Bombay around July the 23 or 24, with this known handicap, under the command of Captain S Prakash with an initial convoy of 700–800 sailors and officers.

The fleet commander joined the convoy with two escort frigates, Brahmaputra and Beas, under Captain JC Puri and Commander LN Ramdas. Some Sea King Helicopter trials were conducted at Goa. And two Alouettes (Alouette III/HAL Chetak helicopters) came on board. Cochin was reached on July 26. After spending a couple of days there, the ship left for Madras (now Chennai). They docked at Madras by August 1.

Readers may wonder if the convoy faced any risk on the way to Madras as it went round Ceylon without any aircraft on board. It might appear that there was no specific risk perception in the prevailing geostrategic situation at that time.

Madras was the ideal port for preparing for war where they had plenty of berths and port facilities. The aircraft were expected to come on board. They needed to be “worked”. Provisioning was done. It was a good port to be in during monsoons. The Arabian Sea was rougher than the Bay of Bengal. Since the aircraft needed practice flights for gaining familiarity and confidence, calmer waters were needed. A carrier can’t afford to pitch and roll too much while launching its flights or during “recovery”, that is, when they come on land.

Getting ready for the real thing

The ship then went out for a sortie for a couple of days and was confident that the vessel was fully seaworthy as the boilers could sustain it. Then the first planes came. They were the Alizés (Bréguet 1050 Alizé). They had a crew of three at that time, a pilot, a radar operator and a navigator/observer. These were slow, long range planes with a lot of “endurance”. They were meant for reconnaissance and in those days, carried a bomb load of 1000lbs (2 X 500) which could be replaced with rockets if the need arose.

They remind us of the WWII German Focke Wulf, FW 200, Condors and their role in tormenting the allied “Arctic Convoys”. These ships brought essential supplies and equipment to the Soviets, from Scotland, via the freezing waters of the Arctic Ocean. The Condors circled on and on, hour after hour, locating the convoys and bringing in the U-boat packs for the kill! INS Vikrant finally had five Alizés in that operational phase.

Indian carrier INS Vikrant launching an Alizé during the 1971 India-Pakistan war.

Indian carrier INS Vikrant launching an Alizé during the 1971 India-Pakistan war.

The ship had seven ack-ack gun (40mm Bofors anti-aircraft guns) mountings (G1 to G7) with a three-man crew for each gun. These were simple, robust, “see and fire” guns without any electronic or sophisticated fire control system. This, often underrated, piece of armament on a carrier actually played a significant role as we would later see.

After the Alizés, INS Vikrant took on and 18 Sea Hawk fighter-bombers (Hawker Sea Hawk, equipping the Indian Naval Air Squadron 300), in stages, over a couple of weeks. The Sea Hawk squadron (White Tigers) constituted the primary strike force of the carrier.

The role of helicopters was important for the carrier’s operations. They had to stand by at SAR (search and rescue) stations, towards “port” (left of the vessel), during flight launches. The idea was to rescue the pilots of any plane that might hit the water after failed take offs.

For the two months that INS Vikrant was at Madras, they prepared well for the supremely important role they were about to play in the forthcoming struggle. Every Saturday, Vikrant would sail out on exercises and trials. The aircraft would practise flying off and landing. They would practise firing at targets streamed by Vikrant or other ships. The coordination and synchronization of all operational functions would be drilled. They would practise formation flying and fly CAPs (combat air patrols) meant for fleet protection from enemy air action when in the range of the latter’s bases. And also to protect returning strikes in case enemy planes chased them. While at Madras, its third escort, the corvette, INS Kamorta, under Captain MP Awasti came to the party.

They would return to the port on the following Monday, a week after the next, having practised for over eight days. In the harbour, again they would attend to maintenance and logistics for the following five days before sailing out next Saturday, again. This way, Vikrant and its crew got ready for the real thing, for the day of reckoning.

An incident happened at this time that today’s readers may find fascinating. A stellar figure of Tamil politics and cinema, MG Ramachandran, visited the ship. He didn’t identify himself as a VIP or a star or an MLA to the Midshipman on duty, but simply said that he is an admirer of the navy and has come to visit. Under instructions of the ship’s deputy commander, he was taken to the quarter deck and offered refreshment. Never once did he let out his importance or stature. He offered them some unreleased Tamil movie spools made by him, which caused great delight amongst the crew members who could speak the language. One can only wonder how far Indian public life and public figures have come since then.

INS Vikrant is combat ready

Finally, by the end of September, Vikrant was ready for war. They had the best amongst the best as air crew for the planes. Because of the less than ideal conditions on board, only veteran pilots were assigned so that operations could be conducted successfully amid all challenges. In Pakistan “Crush India” stickers appeared on the rear windows of motor vehicles at around this time. The countdown has begun. Fed by misrepresentations about how the war in 1965 actually went for their country, the West Pakistanis were raring to go. They wanted to complete the unfinished business of 1965. And their terrible angst against the “traitors” in the eastern half of the country added to the war frenzy.

Sailing from Madras, they approached Visakhapatnam, where Vice Admiral Nilakanta Krishnan, the flag officer commanding in chief, Eastern Naval Command, supervised some exercises in which Vikrant and other ships participated. After spending some time in anchorage off Vizag, where some bits of maintenance work was done on the ship, they returned to Madras. An entire month of October was spent in Madras. In the meantime, the Eastern Fleet was formed, on November 1 with Rear Admiral Sree Harilal Sarma as the commander.

Sometime in early November, Vikrant sailed off to Port Blair with its entourage and spent the next couple of weeks. While at Port Blair, the INS Guldar (L13) and INS Gharial (L12), two LSTs (landing ship tanks) meant for specialized amphibious operations joined Vikrant with supplies and replenishments for ammunition and stores consumed during the exercises. The exercises went on constantly honing the skills and capabilities of men and machine.

While in Madras, some Gorkha infantry troops had come aboard Vikrant.[1] While the rest had boarded the LSTs, these troops would play an important role in the forthcoming operations.

By this time, Pakistan had decided to risk its ageing submarine, PNS Ghazi, to hunt down Vikrant, in the eastern waters. Hence, Ghazi was sent on November 14 to be in place for a pre-emptive strike on Vikrant at the outset of hostilities. The Indian navy anticipated the Pakistani move and hence tried their best to keep Vikrant’s location a mystery, moving it all over the chequer board of Bay of Bengal. Thus both sides had staked their ageing aces for a decisive showdown in the east, where the fate of the subcontinent was to be decided shortly.

PNS Ghazi.

PNS Ghazi.

INS Vikrant goes into hiding

As November rolled on, the naval command, increasingly wary of the risks of Vikrant getting located and tracked by Ghazi, sent the carrier off, along with its escorts to the remote Port Cornwallis, in North Andamans, a perfect hideout for the carrier and its ss entourage with lots of greenery, no local populace and nothing to give them away in those days before the advent of military satellites. It was an absolutely deserted and uninhabited little nook with a picturesque bay and a lone jalebiwala. He became the sole means of sweetening the war for the sailors and officers of the battle group, in the last days of November 1971 as the clock ticked towards 0 hour (midnight).

The harbour of Port Cornwallis, island of Great Andaman, with the fleet getting under way for Rangoon. (Photo courtesy: British Museum.)

The harbour of Port Cornwallis, island of Great Andaman, with the fleet getting under way for Rangoon. (Photo courtesy: British Museum.)

Open Sangsar: The beginning of the end

They went out on December 2 for some more exercises, including night flying. After it was all done, including the “Flying Stations”, the carrier turned back for Port Cornwallis. A few of Vikrant’s officers and members of the Eastern Fleet staff were on the bridge for 8-12 pm watch. It was a lonely hour on deck. India and Indians at home went about their business as usual. There was talk of war everywhere but nothing was happening that one could see. Pakistan Air Force’s (PAF) planned Operation Chengiz Khan was almost 24 hours away, the planned “surprise” airstrike against the IAF’s forward air bases stretching from Jammu & Kashmir (J&K) to Gujarat. Neither a single Pakistani tank or infantryman approached Indian positions in the west, nor a single artillery shell fired. In the east, the usual skirmishing went on inside the border areas as the Mukti Bahini, with Indian help, stepped up the pressure.

That was when a signal was received at Vikrant’s bridge from naval command. It simply read “Open Sangsar”! It was handed over to the OOW (officer on watch) who couldn’t make anything out of it and was like “pata nahi kya hai (don’t know what it is)!” He consulted the navigating officer. He too was puzzled. They called the Ship’s captain, who asked them to immediately send it over to him. Upon receiving it, he knew what to do with it. It referred to one of the several envelopes in his safe, the one marked “Sangsar” that had been given to him by the Naval Command to be opened only upon receipt of this code. Captain Prakash opened the envelope and the order to commence hostilities stared back at him.

We are thrilled and glad to be able to bring this stunning bit of history to our readers. Contrary to what most people know about the 1971 Indo-Pak war, India was not surprised by Operation Chengiz Khan the next day. Neither did that failed “surprise” strike by the PAF, actually it triggered hostilities. India had beaten Pakistan to it by a full 24 hours. The trump card in the east had been dealt. The move that was to finally seal East Pakistan’s fate had been made. Vikrant was on its way to take up position near the Chittagong coast to seal off the sea route to, and from, East Pakistan. And to launch repeated air strikes against the Pakistani coastal defences, ports and installations, the die was cast.

There is reason to believe that Indian intelligence planted misinformation in Pakistani decision-making circles which caused them to launch their pre-emptive strike on December 3, a day after the Operation Chengiz Khan was originally planned. Indian intelligence played a crucial role during the period. According to Gen JFR Jacob, chief of staff, Eastern Command: “On 1 December, we intercepted a message from West to East Pakistan advising them of the warning sent to all Pakistani merchant shipping not to enter the Bay of Bengal. We passed this onto the three service headquarters – Army, Navy and Air Force, as also an intercept warning civil aircraft not to fly near the Indian borders.” One way or the other the Indian high command (the highest echelons of the Indian armed forces and government) was wise to the fact that Pakistan was about to launch hostilities by December 2. They lay in wait.

Captain Prakash came up to the bridge right away. The fleet commander, Rear Admiral Sarma, was informed. The course of the battle group was altered and set towards the Chittagong area. The next morning of December 3, the first thing Captain Prakash did was to inform the crew over the carrier’s PA System that their orders had come, they were headed for combat now towards their area of operations and the first air strike will be launched at 0600 hours on the December 4 morning with eight sea hawks on Cox’s Bazar. He spoke with clarity, firmness and was to the point, leaving no one in any doubt about what the mission was and how it was going to be. The sailors and officers were in high spirits and there was a round of hand shaking and rejoicing that finally they were going into action.

The White Tigers leap

In the event, on the early morning of December 4, the first sortie couldn’t go in as planned at 6am. It was launched around 8am while the carrier closed in with the coastline for the launch, from the usual distance of 230-plus miles they usually maintained during operational deployment. The AA gunners were at their “action stations” when the Sea Hawks were launched. Their role was important when the sortie was returning (an hour or so after the launch). Their orders were to anticipate enemy aircraft chasing their planes but not to open fire till ordered for fear of engaging their own boys in friendly fire.

This first sortie was important. This was the first action in this war. For many young officers and sailors, it was their first action ever. For Vikrant too it was the moment of truth. After sitting out the 1965 India-Pakistan war, this was their chance to prove themselves and vindicate the risk taken by naval command in sending a slightly handicapped carrier to war.

The first strikers returned in batches. One Sea Hawk came in late, causing some anxiety, but everything was alright in the end. Reports claim Chittagong harbour too was hit that day by Vikrant’s planes.

While INS Vikrant braved the odds and completed its first mission of the war successfully, what was happening to its supposed nemesis, the Pakistani Submarine PNS Ghazi, sent specially to hunt it down? Deploying the ageing Ghazi was also a gamble for the Pakistani naval command, like sending the limping Vikrant was a risky proposition for the Indians. Ghazi had been pulled into a sucker trap around Visakhapatnam by the Indian Navy. Heavy signals traffic had been generated in that area involving the INS Rajput and other vessels. Ghazi fell for the illusion that its target, INS Vikrant, was to be found there. And it was in that area that Ghazi went down on the night of December 3 and 4 while laying mines in the sea, done in by mysterious events, which till date haven’t been clarified to the satisfaction of all concerned.

In the meantime, Indian Navy frogmen (commandos) along with the Mukti Bahini were bringing shock and awe to the Pakistani Naval vessels and installations in the Khulna and Chalna port areas. The next day, there was another mystery involving a submarine, the news of Ghazi going down was not known at this time. On December 5 morning, Vice Admiral Krishnan, flag officer commanding in chief, Eastern Naval Command, sent a signal to Naval Headquarters: “I have a submarine at my doorstep.” At that time it was thought to be the Ghazi. But since we know now that Ghazi had already been sunk, what could that mystery submarine be all about?

Again on December 6 or 7, there was a submarine alarm. INS Beas caught suspicious movement on its Sonar. So, Brahmaputra and Beas went looking for it. In the meanwhile, INS Kavaratti, an anti-submarine corvette, minus its sonar but with two 76.2mm radar-controlled guns had joined the battle group. They too joined the hunt. Vikrant itself was running at its maximum possible speed extracted from those three boilers, around 16 knots. But after running for close to an hour, they gave up. Captain Prakash told the fleet commander that no submarine could have possibly kept up with their recent dash and it was time to launch their planes for the next sortie. Admiral Sarma gave the go-ahead and Vikrant turned into the wind and launched the sortie.

It is to be noted here that the carrier’s launches were scheduled and synchronized with the IAF in order to ensure that there was no confusion between friendly aircraft running into each other at the same place at the same time.

INS Kavaratti somewhere in the east, in 1971,

INS Kavaratti somewhere in the east, in 1971,

The noose tightens

By that time INS Vikrant started encountering neutral shipping in the waters close to East Pakistan, no one had any idea about the blockade. They were stopped and their credentials checked. Those that were going towards East Pakistan, if found genuinely neutral, were allowed to turn back. One such ship was trapped and had to be abandoned. The Alizés played a very important role here with their long range and slow speed for a thorough reconnaissance and scan of the Bay of Bengal. With growing confidence, Vikrant had started getting real close, within about 60 miles of the coast. No enemy air attacks had come in, the PAF Sabre Jets had been shot out of the sky by then and with the Ghazi gone, there was no real danger any more. However, there was not too much rejoicing since the Ghazi’s sinking was followed by the loss of INS Khukri in an epic duel with the brand new Daphné-class Pakistani submarine, PNS Hangor, in the west with 194 dead.

PNS Hangor in 1971.

PNS Hangor in 1971.

No escape for Pakistanis

One morning (most probably December 10) when they were headed for breakfast, there appeared two Pakistani troop ships (actually merchant ships, Anwar Baksh and Baqir) on the horizon with around two thousand troops from the Baluch Regiment, trying to get away. They were accosted and stopped by the battle group. INS Brahmaputra sent across a boarding party under Lieutenant Commander Bajaj. The boarding was resisted, attempts were made to snatch weapons, so our personnel opened fire leading to a loss of some lives on the other side. The two ships were then escorted over to one of the Indian ports in the east.

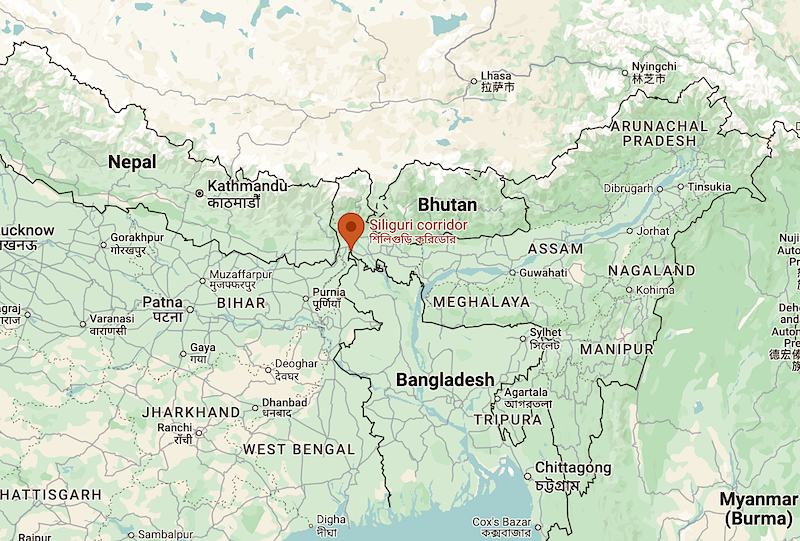

This kind of a tight blockade and the inability of their personnel to escape the Indian dragnet in the Bay of Bengal had a singularly demoralising effect on the Pakistani command in the east. Here, we come back to the subject of the Gorkha troops picked up by the LSTs earlier. This is a fascinating chapter by itself, the story of Operation Beaver. 1/3 Gorkha Rifles and some troops from Bihar Regiment joining later from Bengal Area command, composed the “Romeo Force”, meant to stop Pakistani troops from escaping into Burma (now Myanmar) using the WWII Arakan Road. According to some, this was Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw’s personal project on which he put a great store in keeping with his focus on the Chittagong sector in the war in the east. He had this concern that Chittagong could become a point of ingress or escape for the enemy.

By all accounts this mission didn’t go too well. By the time it was launched south of Cox’s Bazar (Reju Creek) on December 14-15, the Pakistani forces were at the end of their tether and the town was in the hands of the Mukti Bahini. This amphibious operation was launched without the requisite beach survey and had little information on the local conditions. The two Landing Crafts ferrying the Gorkhas landed them in seven to nine feet of water with their packs and equipment. Two men drowned before a platoon got ashore and a patrol reached Cox’s Bazar finding no enemy there.[2]

However Operation Beaver’s insipid showing didn’t alter the facts on the ground, as far as limiting the escape route to Burma is concerned. Brigadier SS Uban’s SFF (Special Frontier Force) units operating from Marpara, Demagiri, Bornapansuri and Jarulchari, across the Indian border successfully pushed back the Pakistani force from the CHT (Chittagong Hill Tracts) area between Chittagong and Burma. Once the Dohazari bridge was destroyed and Rangamatitown captured, the southern escape route was largely untenable for the Pakistanis in spite of the late Indian arrival at Cox’s Bazar.

Areas of East Pakistan (Bangladesh) adjoining Burma (Myanmar).

Areas of East Pakistan (Bangladesh) adjoining Burma (Myanmar).

The mob gangs up

Now, we come to that part of Indian military history which generations that came later will find difficult to even envisage. When Pakistan’s US-led western allies found it impossible to stymie India in the UN due to the steadfast Soviet support. US President Richard Nixon implored China to threaten India on the line of actual control (LAC) and thus divert forces from the Pakistan operations. China, of course, unlike the current time, was quite wary of Indian capabilities. Particularly after being rebuffed by Lt Gen Sagat Singh in Sikkim during the 1965 India-Pakistan war and then getting a bloody nose at the same place (Nathu-la) in 1967. To top it all, they knew that Soviet forces were lying in wait at the Xinjiang border to the north-west. So, the Dragon preferred to keep away.

In sheer desperation, when their Cento (Central Treaty Organization) plus Seato (Southeast Asia Treaty Organization) ally in this strategically vital region was crumbling and about to be dismembered, the US and its cohorts tried a stunt that the world had not seen since the Suez crisis. In 1956, the UK and France, in support of their regional client state, Israel, attacked Egypt in the canal area, in pursuit of their geostrategic interests. This time the US and the UK decided to send their navies to scare India off and to stop it from delivering the coup de grace in East Pakistan. India’s treaty bound friend, USSR, in turn, sent their ships to the Indian Ocean area to prevent the western allies from hobbling India.

Those were tumultuous days for all Indians who had an eye on the war. Rumours floated freely as it was officially announced that the US seventh Fleet was on its way from Southeast Asia. Followed by vague information about a Soviet task force following. How was the news received by the men and officers aboard INS Vikrant? We learn that officially nothing was announced by the ship’s captain or the fleet’s commander to the crew. But they heard the radio and so they knew what was brewing.

The failed ‘Enterprise’

In reality, the US government at the highest levels had decided to come to the aid of Pakistan. On December 10, the formation and movement of US Naval Task Group 74, a part of the Seventh Fleet, was officially announced. It comprised of the nuclear powered aircraft carrier, Enterprise, an amphibious assault ship (USS Tripoli) with a marine battalion and 25 assault helicopters, four guided missile destroyers (USS King, USS Decatur, USS Waddell and USS Parsons ), four gun-destroyers (USS Bausell, USS Orleck , USS McKean and USS Anderson), nuclear attack submarine USS Gurnard, supply ship USS Wichita and munitions ship USS Haleakala.

That a nuclear attack submarine (SSN) was part of the group has been confirmed by the commander, Submarine Group 7.

The terse communiqué said it was heading towards the Bay of Bengal.

In his book – “Pakistan’s Crisis in Leadership”, Major General Fazal Muqeem Khan wrote: “On December 12, the CGS sent a telephone message in Pashto informing (Lt Gen) Niazi that friends – ‘yellow from the north and white from the south’ – were coming by midday December 13. The next day a message from GHQ indicated that the friends would be delayed by 48 hours.”

USS Enterprise.

USS Enterprise.

Admiral Elmo Russell “Bud” Zumwalt, chief of naval operations, United States Navy, in his memoirs – “On Watch”, wrote: “The naval situation in the Indian Ocean just then was complicated and confusing. Quite by chance, a large British navy task group, including two carriers, the last ships of the British fleet to remain east of Suez, was on its way home through the Indian Ocean at the time India marched into East Bengal. Two days after that invasion, a Soviet destroyer and a minesweeper came through the Malacca Straits whose mission had been to relieve the destroyer and minesweeper that had been on station (in the Indian Ocean) for six months. In view of the war, the relief became reinforcement; the original contingent stayed on. Furthermore, on December 6 or 7, the Russians detached a cruiser armed with cruise missiles, and escorts for it, from their Pacific Ocean Fleet and sent them towards the Indian Ocean. They were sighted by the Japanese in the Straits of Tsushima on 9 December. Though these ships did not reach the Malacca Straits until December 18, we of course knew they were on their way …

On December 10, a presidential order that was not discussed with the (US) navy in advance, created Task Group 74, consisting of the nuclear carrier Enterprise and appropriate escorts and supply ships and sent it steaming from the Gulf of Tonkin, where the ships had been on station, to Singapore. The order did not specify what TG 74’s mission was, nor could anyone, including the chairman of the joint chiefs, tell me. I sought to be sure that these ships either had a mission or were not sent in harm’s way. The ships were held off Singapore for two days. On December 12, they were ordered through the Malacca Straits into the Indian Ocean. That order was rescinded within an hour only to be reissued the next day with an additional proviso that as much of the passage through the Straits as possible be in daylight, i.e., in full view of the world. At the same time “sources” in Washington let it be known that the object of the exercise was to cover the evacuation of American civilians from Dacca in East Bengal. This clearly was a cover story since that evacuation, after having been impeded by the fighting for a week, was successfully completed two days before TG 74 entered the Indian Ocean.”

So, it is clear that the US Task group meant business and though its land warfare capability was limited to one Marine battalion, it was packing a formidable punch in terms of air and sea combat power.

This then was what INS Vikrant’s battle group would have faced if push came to shove. Well it didn’t in the actual turn of events. But in those December days and nights, as the US Navy’s TG 74 closed in, it was a reality.

In the meantime, a Soviet naval task force from Vladivostok consisting of a cruiser, a destroyer and two attack submarines (cruisers – Dmitry Pozharsky, Varyag, BPK Vladivostok, destroyer – Strogiy and two EM Visky (Whiskey-class submarines) under the command of Rear Admiral Vladimir Kruglyakov was despatched to counter the dual threat of the US fleet and British navy’s carrier task force. The Soviet vessels are said to have intercepted TG 74. Rear Admiral Kruglyakov Vladimir Sergeevich, commander of the Soviet navy’s 10th Operative Battle Group (Pacific Fleet), described in a TV interview, the encircling of the task force, surfacing his submarines in front of the Enterprise, opening the missile tubes and blocking the American ships. However, US sources recounted the encounter on December 19, after the Bangladesh war was over.

Stabilized targeting post on the Dmitry Pozharsky cruiser.

Stabilized targeting post on the Dmitry Pozharsky cruiser.

In his memoirs, Rear Admiral Kruglyakov writes:

“I was ordered by the Chief Commander to track the British navy’s advancement. I positioned our battleships in the Bay of Bengal and watched for the British carrier ‘Eagle’.”

However, this force was thought to be vulnerable to the HMS Eagle’s strike power. Hence, to augment them the task force was sent from Vladivostok.

Faced with this dual threat, the British navy called it a day and retreated South West, out of harm’s way.

On the threat from the American TG 74, Admiral Kruglyakov said, “I had obtained the order from the commander in chief not to allow the advancement of the American fleet to the military bases of India …

… We encircled them and aimed the missiles at the ‘Enterprise’. We had blocked their way and did not allow them to head anywhere, neither to Karachi, nor to Chittagong or Dhaka …”

The chief commander had ordered me to lift the submarines and bring them to the surface so that they could be pictured by the American spy satellites or could be seen by the American navy. “It was done to demonstrate that we had all the needed things in the Indian Ocean, including the nuclear submarines. I had lifted them, and they recognized it. Then, we intercepted the American communication. The commander of the carrier battle group was then the counter-admiral Dimon Gordon. He sent the report to the US Navy’s 7th Fleet commander: 'Sir, we are too late. There are Russian nuclear submarines here, and a big collection of battleships’.” This last supposed signal has no confirmation from the US side, as stated above, since the crisis was over by then.

Thus, the threat of the Seventh Fleet and all the menace it represented, for the Indian war aims, never showed up in the Bay of Bengal. INS Vikrant, its escorts and their sailors and officers, ultimately didn’t have to face the moment of truth. How would they have responded if this much more powerful battle group tried to disrupt the blockade and bail out the Pakistani forces from the east? Surely that would have negated all that they had fought and strived for. The risk of a duel with the Ghazi, the months of preparation and toil to get the most out of a limping ship, the martial satisfaction of humbling an arch enemy when the chips were down and most importantly, India’s long conceived and steadily pursued strategic aim of dismembering Pakistan would have come to a nought.

There can be no doubt that if the American TG 74 had its way, the other side was hoping that there would be an immediate ceasefire, at the least, with subsequent withdrawal of Indian troops from East Pakistan. A moth eaten version of regional autonomy would have been forced down the throat of the Awami League leadership, a lame duck, fledgling Bangladesh administration, which few recognised as of that day, would have had to swallow a bitter pill.

Indian Kamikaze?

How were the mood and morale on board Vikrant, and its escorts, in those days of uncertainty when the outcome was literally “up in the air”. What did the crew and pilots, in particular, feel about the menace of the US Seventh Fleet and all that it represented?

Nobody below the command level was privy to what would actually happen if the USS Enterprise showed up. Or what were the plans of the Indian navy, the armed forces as a whole and Government of India, in such an event.

But what about the personal morale and attitude of the frontline fighting men, who would have faced the brunt of the action if it came to that, do read on to know and feel another saga about the Indian fighting man’s martial instincts when he sniffed blood.

The 200-odd officers on Vikrant had their ward room, with its own dress code. Midshipmen had their own ward room called the “Gun Room”. Middies called it “Snorty”. The pilots were all busy round the clock with multiple flying stations. The fighter pilots in particular preferred to come to the Gun Room for their breakfast to avoid “dressing up” early in the morning with a full fatiguing day ahead. In the evenings too, after the day’s flying was over, they would come down to the “Snorty’ for beer. They would anyway come down to join the middies, carrying their drinks, when their bar was closed for the day.

Usually there would be fun and levity during those sessions. People would sing songs. Shayari (poetry) would start flowing as the evening wore on. But during those climactic days of the campaign, as US TG 74 sailed through the Malacca Strait and closed in, the talk changed. The crew and pilots knew what they would be up against if there was a showdown.

Our seniors, veteran pilots, were unfazed. “Unko aane do, koi baat nahi … Hum dive marenge unke ship mein (Let them come, no issues … we will dive into their ships).” The Indian pilots were mentally steeling themselves for “kamikaze” suicide missions to destroy the much superior USS Enterprise if the Americans came to thwart India’s war aims.

A Japanese plane is shown swooping down on a US warship in the three-day battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944.

A Japanese plane is shown swooping down on a US warship in the three-day battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944.

Experienced veterans call this “war room” talk rather than “ops room” talk. After the passage of five sobering decades, such talks are discounted as being of no consequence. The possibility of any serious plans having been communicated from the top to confront the American ships at that stage, are not considered plausible. That situation had not arisen yet and ultimately never arose. But many readers, who know about the other last ditch actions of supreme sacrifice of our men in arms, may come to their own conclusions about the possible surprise that awaited the Enterprise.

“… the Americans would find in us a Vietnam to end all Vietnams …”

In fact, the mood in the “war room” was matched by the steely resolve in the “ops room”. In his memoirs – “No Way But Surrender”, FOC-in-C Eastern Naval Command, Vice Admiral Krishnan wrote:

“At about 5.30pm on the eighth day of the war, Friday, December 10, we intercepted a signal to the effect that the US Navy was sending ships into the Bay of Bengal, for possible withdrawal of the Pakistan Army. I also spoke to Admiral Nanda regarding the 7th Fleet but he had heard no more than what was in the signal. We ended our conversation on the note that we should not be surprised by anything that happened from now onwards. None of us ever fell for the gimmick that the fleet’s object was to evacuate a handful of American subjects from Dacca. You do not require an elephant gun to shoot at a flea. Obviously, her primary intention was to frighten us into withdrawing our forces from the operational area and let the escape ships break out. Suppose we didn't scare that easily and persisted in our stranglehold on Bangladesh? Evacuation of any but a handful of troops was a possibility, using helicopters. Clearly the use of heavier and very powerful aircraft was quite out of the question as however thorough the temporary repairs, the runways of both Chittagong and Dacca had taken considerable beating.

The offensive capabilities of the fleet, therefore, consisted of: (i) Landing up to a marine battalion as an assault group using helicopters, (ii) Using the Enterprise’s aircraft for ground support role, (iii) Providing close support against aircraft attacking their fleet, and (iv) Surface and aerial attack on Indian warships.

We did not know if the marine battalion was carried on board the Tripoli at the time but even assuming that they were how they were going to land them ashore except by helicopters. It was quite obvious that manpower wise, landing some 2,000-odd persons was not going to materially alter the land battle in which some 93,000 soldiers were gasping for breath. "It was unthinkable that they would commit their aircraft on a ground support role against our army or air force or only attack our naval forces at sea. If they did, it would possibly mean war between the United States and India and, as I said to my colleagues in the Maritime Operations Room, ‘that might mean the end of the world or the Americans would find in us a Vietnam to end all Vietnams’.”

Continuing, he writes:

“To my way of thinking, the most effective method of helping the Pakistanis would be to close Chittagong within range of their air power, put up a formidable air umbrella over the merchant ships awaiting escape and actually provide air escort for them till they reached the waiting fleet. They knew that our tiny force of aircraft from Vikrant could never hope to challenge the air cover and we could at best watch the trapped animals getting away from our clutches …

Summing up the appreciation, we came to the following conclusions: (i) A critical point was being reached in the war and the Pakistanis were desperate and would try to break out at the earliest opportunity. (ii) For this purpose, they had at least five merchant ships ready and camouflaged in Chittagong. They had made desperate attempts to make the runway at Chittagong sufficiently serviceable to take light aircraft and helicopters. (iii) The safe arrival of the convoy RK 623 would be the starting point of putting their ‘Scorched Earth Plan’ into action. (iv) The removal of Vikrant from the scene of operations would ease the way to a break out. The Pakistanis must have hoped that we would withdraw Vikrant to “get out of the way of the Seventh Fleet.” (v) A break-out of ships could be facilitated by the Seventh Fleet providing an impregnable and continuous air umbrella till they joined the surface forces of the Seventh Fleet. Having thought out the various possibilities, it was necessary to plan out our line of action. Clearly, everything turned on the merchant ships assembled in Chittagong for the actual troop carrying. Not an instant must be lost in destroying or so heavily damaging them as to make them totally immobile. Time was running out.

Having spent the whole forenoon of 11 December on the above thoughts and a series of discussions with Admiral Nanda as well as my army colleague Jagjit Aurora, I signalled the Fleet at 1.15pm as follows:

(a) Appreciate enemy with senior officers including FOCEF planning major breakout and will try to get away by hugging the coast. Senior officers may try to escape by air. Approaches to harbour likely to be mined. (b) Your mission: (i) Put Chittagong airport out of commission; (ii) Attack ships in harbour by air and surface units if they break out. (c) This is undoubtedly the most important mission of the war in the East. The enemy ships must, I repeat, must, be destroyed. Good luck.”

So, India was prepared to go the mile, from the highest levels of command to the front line pilots, even if the mightiest adversary on earth came in to intervene. The collective mood of the Indian armed forces that time can be summed up in the French commander Marshal Philippe Pétain’s immortal World War I order of the day to the defenders of Verdun: “Ils ne passeront pas (They shall not pass).”

After the west had been permitted to evacuate their citizens from East Pakistan early in the war (though 47 US citizens remained in Dhaka), no more flights were allowed to get away. A UN C 130 Hercules aircraft tried to fly away one of those days. The gun crew of one of Vikrant’s AA guns (G-5) opened up spontaneously before they were asked to stop. Two of the Sea Hawks scrambled to intercept. But the UN plane had turned back towards East Pakistan by then.

A farewell to war

Going beyond the “what if” speculations, the war was now drawing to a close for INS Vikrant. No enemy could finally pass. India’s war aims were on the verge of meeting success.

On December 14, with Total Victory in the east on the horizon, Vikrant came to Paradeep to refuel. All these days, the SCI tanker Deshdeep, commanded by officers of the Indian Navy, was being used to refuel the other ships in Vikrant’s battle group. But Vikrant herself did not require refuelling, as it was operating with three boilers only. While at Paradeep, Vice Admiral Krishnan came on board and congratulated everybody and displayed the side arm of his surrendered Pakistani counterpart from their eastern naval command. The Pakistani forces in the east had surrendered on the afternoon of December 16.

From then on, they sailed to Madras via Vizag. Parties were organised at Madras for the returning victorious warriors. India was welcoming home her heroes who had given the country its greatest military victory ever.

As we wrap up this story of one of the greatest-ever geostrategic triumphs in modern times, we would like to reiterate that this is not meant to be another chronicle, rich in archival facts and details. There are numerous accounts of the India-Pakistan war of 1971 and the liberation of Bangladesh. Many of those are far more detailed and true to the minutiae of history.

This story is more about the “Psychological truth” of history, using the words of James P O'Donnell, the author of “The Bunker”, on Hitler’s last days in Berlin. He wrote this, immediately after leaving the US army at the end of World War II, based on interviews of those who had experienced events first-hand, during those last days in Hitler’s bunker. He said about his book:

“Just how close this composite account comes to historical truth, to the kind of documentation an academic historian insists on, I simply cannot say. Nor is it overly important to my purpose. I am a journalist, not a historian. I ring doorbells; I do not haunt archives. What I was looking for is, what I believe many people look for, psychological truth. [Emphasis ours]”

Notes:

[1] There is controversy regarding when the Gorkhas boarded Vikrant. There are other versions which talk of the “Romeo Force” being put together in West Bengal and despatched to Cox’s Bazar directly at the time of the operation.

[2] There are various versions about this particular operation and the casualties by drowning.