India is witnessing a raging debate on the subject of permanent commission (PC) for women in the Army. The arguments range from the sexist to the feminist, with politically correct (PC) doublespeak in between.

Can there be permanent commission for women, at par with men, without putting them in combat roles, at the front? Will it be fair for the military’s morale to give permanent commission to a class of citizens who would be sheltered away from the “real thing” – the risks and glory of frontline combat?

While the Colonel Suresh Babus fight and die at the front, should another group of officers be allowed to risk lesser hazards while getting the same privileges?

The traditionalists feel that women are not suitable for war, except in the stereotypical “nursing and switchboard” roles. Some even quote tired old shibboleths about “who will bring up the next generation of citizens if mothers go to war?!”

On the other side of the spectrum, feminists advance their theories of “empowerment through entitlement”, which translated into layman’s language means artificial “equality of benefits” without “equality of effort”. Quite simply: “Don’t have to send them to war but do give them the glory of the warrior!”

If we step out of this slightly nauseating set of exchanges and take a look at the empirical facts about women at war, we may get a better perspective on the issue.

Have women gone to real wars? Not the exceptional super woman but the girl next door? How have they fared on the battlefields of history? What kind of societies sent them to war, under what circumstances?

Ancient history and mythology

We have heard of the mythical Amazons who lived and fought by the Thermodon river. A warrior tribe of women who lived to be soldiers.

Sculptures depicting Amazonian women warriors.

Sculptures depicting Amazonian women warriors.

But coming to the modern times of documented history, what we do have?

World War II

The Soviets used women in combat roles extensively as members of Partisan units operating behind German lines. They fought and lived along with their male comrades, shared the risk and hazards and yes the glory too! But what about the regular army? 800,000 Soviet women served in the Red Army. Out of them 200,000 were decorated and 89 got the country’s highest military honour – “Hero of the Soviet Union”.

Apart from the usual tasks as doctors, nurses, auxiliaries, etc, they served extensively as combat pilots, frontline snipers, machine gunners and tank crew. Lyudmila Pavlichenko, the most successful female sniper of all times, had 309 confirmed kills.

Lyudmila Pavlichenko.

Lyudmila Pavlichenko.

And there has seldom been a soldier as brave as Soviet machine gunner Manshuk Zhiengalikyzy Mametova, the first Asian (Kazakh) woman to be awarded the Hero of the Sovet Union decoration (posthumous) after her legendary last stand at Nevel, on October 15, 1943. During a ferocious German counterattack to retake a hill, Mametova refused to fall back with the rest of her unit and alone manned three machine-gun nests, moving from one to another under a hail of mortar and artillery barrage. She finally fell but not before accounting for 70 of her enemies.

Today, many streets and schools in Kazakhstan have been named after her, and monuments in her honour are found in many parts of the former Soviet Union.

Manshuk Zhiengalikyzy Mametova.

Manshuk Zhiengalikyzy Mametova.

But stories of WWII can’t be complete without a German character featuring in it. That brings us to the incredible tale of Werwolf Hauptgruppenführerin (Captain) Ilse Hirsch and her act of extreme courage (though wielded in a wrong cause) in Unternehmen Karneval (Operation Carnival). She was a member of a stay-behind commando force called “Werewolves”. She and five others were parachuted behind enemy lines for an assassination mission against the US-installed mayor of Aachen, a German city captured by the allies.

That was a time when the Germans were losing the war and the mission was deep behind American lines. She played a critical role in the mission and escaped after its completion despite sustaining a knee injury from tripping over a mine. Born in 1922, Ilse Hirsch lives to this day.

Ilse Hirsch on the cover of a 1940 German propaganda magazine.

Ilse Hirsch on the cover of a 1940 German propaganda magazine.

Those were desperate times for their nations when to each, the survival of the country was at stake. Nazi Germany was otherwise traditional in its approach to gender stereotypes. Exceptional women, like the legendary pilot Hanna Reitsch, made their mark on the German military. But as a rule, women weren’t expected to fight. So the story of Hirsch was part of the typical, last-ditch survival throes of a desperate society.

The Soviets employed women on a much larger scale in combat roles in the war, but once it was over, old attitudes returned.

Vietnam War

The decadelong Vietnam War saw an extensive use of women combatants in the ranks of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam – the South Vietnamese guerrilla force which was also known as NFL or the Vietcong – and their allies, People’s Army of Vietnam – the North Vietnamese regular army or the PAVN. They fought as soldiers, saboteurs, agents, logistics support and in air-defence posts.

Two Vietnamese girls handling a machine gun during the Vietnam War.

Two Vietnamese girls handling a machine gun during the Vietnam War.

The extremes of courage, cruelty and suffering that women in the Vietnam War experienced, are in keeping with the unique nature of that unequal struggle against a superpower.

A Vietcong woman guerrilla fighter.

A Vietcong woman guerrilla fighter.

Of the 11,000 women reported to have fought in the war, the gun became a 24/7 companion since there never really was a “back area” free from US air attack or chopper-borne incursions.

Women peshmerga fighters of Kurdistan

They are meant to die. Literally, in Kurdish, “pesmerge” means “those who face death.” Once you read the story of Kurdish women serving in the various militia forces in northern Iraq and Syria, you would never again believe in the sexist gender stereoypes or feminist spiels on “empowerment through entitlement”. With just 45 days’ basic training in infantry weapons, they are sent to fight dreaded jihadist groups, like the Islamic State, and even regular armies.

Margaret George Shello is the most famous woman peshmerga. Also known as Margaret George Malik, this Assyrian woman joined the Kurdish peshmerga forces against the Iraqi governments in the 1960s. Her non-Kurdish background allowed Shello to be accepted in the peshmerga, which at the time was unwelcoming to ethnically Kurdish women. Shello was assassinated by her own side in 1969, in her sleep. Circumstances that led to her early death are still disputed. She was around 27 then.

After her death, legendary tales of her bravery spread through the region and inspired countless Kurdish men and women to join the resistance against the Iraqi governments through the decades.

Margaret George Shello.

Margaret George Shello.

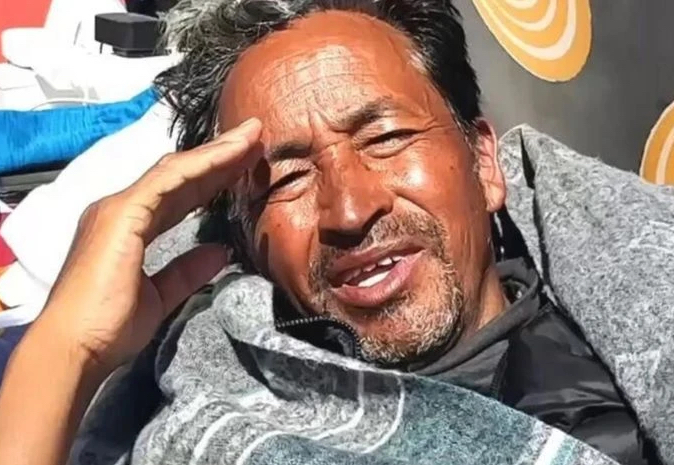

Among the contemporary women fighters in Iraq, Khatoon Khider, the famous Yazidi singer-turned-soldier, is a celebrity. She promised never to sing again till her people were liberated from the clutches of the Islamic State. She is an inspirational figure for women fighting against the terror of the jihadist group.

Captain Khatoon Khider (R) with other women peshmerga fighters.

Captain Khatoon Khider (R) with other women peshmerga fighters.

Apart from those who are under the limelight, there are many unnamed and unsung who have been at the front, and who spent their entire lives in deadly combat since they were young girls.

So coming back to the original proposition of permanent commission for Indian women joining the Army, well, does our debate make sense at all?

If women fight, they will get ranks, badges and commissions, like all other fighters. And women can fight. Question is: will they fight for the Indian Army? Would the Indian society allow them to fight? And most importantly: do they themselves want to fight at the frontlines – on equal terms, as equals?

[Disclaimer: Views expressed by the author are his own and don’t necessarily reflect the views of India Sentinels.]